Organizing Our Marvellous Neighbours:

How to Feel Good About Canadian English

A new book by Joe Clark about Canadian spelling

What’s new

Or buy the book, learn about it, find out what’s new, read the offsite blog, download the raw data, read the errata, or contact the author

Transcript of my appearance on TVO

On 2009.01.31, I appeared on TVOntario’s current-affairs show The Agenda with Steve Paikin. This page offers an annotated transcript (with corrections).

PAIKIN: And joining us now… Joe Clark, author of Organizing Our Marvellous Neighbours. Good of you to join us at TVO. How are you?

ME: I’m fine, thank you.

— Well, I want to talk to you about spelling, Mr. Clark. You wrote a short E-book on the subject of Canadian spelling.

— Mm-hmm.

— What is Canadian English spelling?

— Uh, it’s an amalgam of U.S. and U.K. forms. Just like our history itself, we have a combination of the British influence and the American influence on our spelling.

— Are we 50/50? 60/40? What’s the ratio?

— Uh, it comes close to 50/50, actually, [in the relevant categories where variation exists] if you break it down.

— We speak what could be interpreted as American English; we write a mixture of British and American, I think. How different is British spelling from American spelling?

— Uh, significantly, because you find it in a lot of suffixes like -ise. The British tend to write a word a word like organize as O-R-G-A-N-I-S-E. Americans write I-zee-E. But Canadians have adopted the American spelling – but of course we call a zee a zed. So organize in Canadian is spelled I-zed-E. In British, colour is spelled with a U; in Canadian, colour is spelled with a U. So right there we have an American trend, which is the -ize spelling, and a British trend, which is an -our spelling.

— Do you know how these differences came about in the first place?

— Well, actually, yes, of course, there is the founding myth of Canada – that we come from two peoples, British and French. I think a lot of aboriginal people in Canada would have some issue with that. But in fact in the 1780s, tens of thousands of Americans came to Canada, the so-called Loyalists. They were loyal to the British crown. The War of Independence in the United States had just ended and their side lost, essentially. They wanted to go somewhere where they felt welcome. So about 50,000 of them came to New Brunswick, in fact, mostly, in the 1780s. And they were a large influence on our language. They brought their accent with them and they brought their spelling with them.

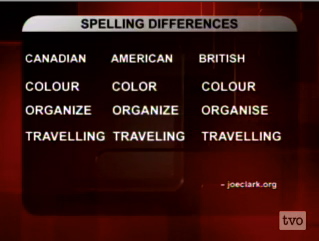

— Hmm. Let’s just do some visual reinforcement of that which you’ve just said.

— Hmm. Let’s just do some visual reinforcement of that which you’ve just said.

— Sure.

— And, Michael, we’ll bring these up right now. Here’s a few words. You’ve touched on a couple of them already. As we look across: Canadian spelling, American spelling, and British spelling. There’s colour with the U as we are supposed to do it; without the U as the Americans do it; with the U as the Brits do it. How about the next one? Organize, as you mentioned, with the zed; with the zed in America—

BOTH: Or zee.

PAIKIN: And with the S at the end of the word as the British do it. And let’s do one more. Travelling: We’ve got two Ls, the Americans have got one L, the Brits have two Ls. And the title of your book – “marvellous”—

— Yes.

— You do with two Ls.

— With two Ls.

— And I must confess, when I saw the title of your book, I thought: That’s crazy. How could he misspell the title of his own book?

— Well, yeah, it is crazy talk for about 50% of the people who write Canadian English. Because those double consonants in words like travelling and focussed and budgetted – there is no agreement on whether to use one consonant or two. And in all the sources I surveyed, no one had agreement. In other words, we all agreed to disagree on that.

— Do you think it matters whether we, in our daily usage, do Canadian or American or British or an amalgam of all of the above?

— Well, Canadian is the amalgam of the British and American spellings.

— Well, I mean pick and choose, as it were.

— Uh, well, no, because then you’re not being consistent. Canadian spelling is a historical fact. It’s been stable for generations. The reason why we would continue to spell Canadian is because we always have spelled that way. Because the correct way to spell is the way everyone else does. And we’ve always spelled this way.

— But what happens when – and I think it’s probably in the process of happening – what happens when students start spelling colour without the U on a test and they’re all doing it, so if the idea is whatever’s the most popular is right, does that student get marked off for spelling colour without the U?

— Uh, presently, yeah. Uh, in a hundred years, color without the U may be the dominant Canadian spelling. But I do take issue with your premise, because I did a lot of checking of Canadian blogs, for example, and Canadian spellings are rock-solid with Canadian blog writers, just as they are with, say, professional journalists and other so-called edited copy.

— But you do believe in a living, breathing language that can, if it wants, to over time change the way it spells words?

— It must. Spellings always do change.

— OK. How about spellchecks? I think one of the reasons I think we here at TVO probably, when we are writing our scripts and so on, spell the American way is that our spellcheck is American.

— True.

— Is there a Canadian spellchecker? I haven’t found one, I don’t think.

— Uh, some software programs do have Canadian settings for spelling. Microsoft Word for Windows can be instructed to start spelling Canadian. The problem with spellcheckers on the whole, including that one I just mentioned, is they are more – they’re too permissive. If a word is spelled correctly anywhere in the world, they’ll just let it go through. So you may spell colour with a U, and that will just pass right through, but you may spell organize with an S, and because the British spell organize with an S it is deemed correct by your spellchecker. So the problem with the computer spellchecker is excess laxity; they’re too permissive. That is actually the thing that might cause more change in Canadian spelling traditions than any other factor. If people keep using computers to write with for the next hundred years, as they surely will—

— Mm-hmm.

— That may cause Canadian spelling to change more than any other factor.

— I don’t want to be a pedant about this, but I can’t spell behaviour with a U without it putting that red line underneath. Or endeavour with a U without getting that red line underneath.

— Right.

— And that bugs me. When I look at that, it bothers me.

— It should, but it’s not your fault. It’s the fault of the user interface of the program. The program should be able to tell you’re in Canada and should automatically set you up to use Canadian spelling. It’s just that it doesn’t do that and it defaults to American.

— I know you touch on Internet, but let’s do a little more on this. Has the Internet affected the way Canadians spell?

— Not according to my research. Canadian spelling is rock-solid even in things like 140-character Twitter postings. People still spell Canadian there.

— Hmm! Do you think Canadian spelling is at risk?

— Uh, the largest single threat is Americanized or Anglicized spellcheckers, which are too difficult to alter the settings of, right? You don’t even know how to turn them into Canadian even if you wanted to. That would seem to be the biggest “threat.” I think the spoken English that you and I are using right now will remain rock-solid for centuries. Canadian spelling is going to change slowly, as all spelling has, right? I think that in a hundred and fifty years, there will be simple things, like the word through is just gonna be thru, and Scarborough really won’t have a -ugh on the end by, let’s say, the 2300s.

— How about night? Will it ever be nite?

— It quite possibly might. That might be an acceptable alternate spelling. We do have alternate spellings for some words in English. Canadian English is not “under threat.” It is – one of the surprising things to people is that Canadian English exists in the first place. It’s been pretty solid for generations and will continue to be solid – with some erosion on the corners, just the way all English dialects have.

— So the notion of it being at risk is really not correct in the first place?

— It’s a misnomer. I think people should not worry about Canadian English being at risk. They should remind themselves that it exists. It is a thing that Canadians are using already. It is a truth of the world. So they should revel in that. It gives us another way of being distinct from the Americans and the British, and we love those, right?

— We should revel in that.

— I think so.

— And if you want to say revelling, how would you spell it?

— Two Ls. [Paikin laughs] That’s a personal choice. Out there in the viewing audience, if you mark it with one L, I won’t write you a letter telling you you’re wrong.

— Now if you want us to continue to spell colour C-O-L-O-U-R and not spell through T-H-R-U, how should we go about preserving that?

— Through usage. Through usage. Uh, as I mentioned before, the correct way to spell is the way everyone else spells. So if you want other people to spell colour with a U, you have to write it yourself. Because you become part of the usage. Correct and incorrect spellings are determined over a long period of time with a large number of usages. And with every blog post you send out, with every Twitter post you send out, with every memo you write at the office, you are contributing to correct spelling. So stick with it.

— Hm. We know that there are other jurisdictions that have significant institutions in place. You think of the French, you know, language, in France—

— In France, yes, and in Quebec.

— And in Quebec, which make sure that the Anglicisms or the Americanisms that have crept into our culture don’t creep into their cultures. Would you like to see something like that in place for English Canada?

— Uh, no, and only from a practical standpoint, not from, say, a standpoint of principle or ideology. I’m not opposed to the idea, but it just wouldn’t work. Because it’s been proposed for centuries. George Bernard Shaw was a proponent of standardized English spelling. Um, it can’t be done. English is too varied. Even within Canada it’s too varied – just the modelling one-L/two-L distinction, for example. You could try it, but it wouldn’t work. The case of French is a bit different because they’re worried about word choices. For “electronic mail” in French, do you say E-mail or do you say the wonderful Canadian word courriel? So their question there is: Which word do you choose? Whereas what we’re discussing now is: Which spelling do you choose for a word you already agree on? That is somewhat different and you couldn’t try to legislate that even if you wanted to.

— Now, normally what happens outside this studio in that green room is off the record. But I’m going to break that rule for this next question.

— How antijournalistic.

— It’s very antijournalistic, but we had a moment back there that was very instructive to this discussion.

— OK.

— Our makeup artist, Diane Rowe – she’s British. She’s lived here for I think 30 years now or something like that? How should she be spelling?

— Uh, either British or Canadian. Since she grew up using the British system and still speaks in British accent—

— She has a very thick British accent. Lovely.

— She has every right to continue spelling British, just as Americans who live in Canada have every right to continue spelling American. But since there are really only three sets of spellings in the English language – which are British, American, and ours, right? – if you’re from another country that is English-speaking, like South Africa or India, you’re really using British spelling. If you were going to hew to anything, you would probably hew to British spelling. But since that isn’t actually your [country’s native or original] spelling, if you come from one of those other countries to Canada you have to convert. But if you’re British or American, you have what could be described as a pure or natural kind of spelling. You could stick with that if you wanted to.

— Yeah, but she lives here now, and she has for a long time. And she’s a Canadian citizen. Shouldn’t she have to spell colo – like, all these words the way we spell them?

— Ah, but it’s like asking her to change her spoken dialect. You learn those things as a child, right, and—

— Oh, no, no, no. It’s – not at all. I’m not asking her to sound like me. I’m not asking her anything, frankly. But I’m saying it’s different.

— She could—

— You could argue it’s different from how you sound.

— Indeed, and she could choose to use Canadian spelling, which would be actually a very minor accommodation for her; she’d have to start using a few more zeds, right? [Pakin chuckles] But I would see no requirement to do that.

— OK. One last question. You know, there are a lot of things under the sun in this world to care about. And spelling is one of those things that fewer and fewer people, I think, care about. I know whenever I try to talk about this with my kids, they just think I’m so old-fashioned and ridiculous. Why do you care about this so much?

— Well, spelling doesn’t matter in some contexts. You should see me typing an instant message. I’ll just let anything through as long as it’s remotely understandable. I have pretty good spelling but bad typing, and those things are often hard to distinguish. There are lots of cases where spelling, in fact, doesn’t matter: Your text message on your cellphone? Spelling does not really matter there. But, say, in business, or at school, spelling is still considered important by other people. So it’s sort of like the lesson from Miss Manners. Manners are there to make other people feel comfortable. It’s the same thing with spelling. Good spelling is there to make other people feel comfortable with what you’re writing.

— Gotcha. I think spelling counts.

— Uh... I do.

— Even if you do spell marvellous with two Ls.

— Yes, I accept you disapprove of that, so I’ll put you in the one-L pile.

— Not disapprove. I’m just – I’m dealing with it.

— You’re in the one-L column.

— Joe Clark, author of Organizing Our Marvellous Neighbours, thanks for joining us on TVO tonight.

— My pleasure.

Corrections

- I didn’t do any systematic data-harvesting and analysis of Twitter postings. I’m going on anecdotal observations here – but the impression I gave is that I rigorously studied Twitter postings. I didn’t.

- I doubt any spoken English dialect will “remain rock-solid for centuries,” no matter what I said to the contrary. But we won’t start sounding like South Africans or Scots.