![[Joe Clark: Accessibility | Design | Writing] Joe Clark: Accessibility | Design | Writing](http://joeclark.org/joeclark-angie-02IX.jpg)

![[Joe Clark: Accessibility | Design | Writing] Joe Clark: Accessibility | Design | Writing](http://joeclark.org/joeclark-angie-02IX.jpg)

This submission is permanently located at the address:

Video samples will be submitted under separate cover. In contrast to the CAB’s airy-fairy assertions that scrollup captioning is just peachy, I have actual proof it isn’t – in the form of the same program captioned in pop-on and in scrollup. See for yourself which version you can actually understand. Intervenors may view those samples by doing what plebes have always been expected to do – schlep down to a CRTC “public examination office.”

While there is some degree of sincerity in the current CRTC process (chiefly on the telecom side), on the broadcasting side the process is really a cover story to push through, with lightning speed, a failed CAB captioning “standard” that is anything but a standard. The broadcasting side of this process was falsely constituted as an open discussion of “unresolved issues” facing disabled people, but is in fact a way for the CRTC to apply a nice coat of paint to an illicit backroom deal.

The intention, at all times, was for the CRTC to engage its friends at the CAB to gin up a failed captioning “standard” to replace the previous one. This new fake “standard,” conjured into life in a secret process by industry nabobs, would then be rammed down everyone’s throats at some future time – presumably during the 2009 licence renewals of major broadcasters.

CAB likes to present itself as a mild-mannered nonprofit organization, but it is really a group of industry lobbyists and enforcers. The purpose of industry lobbyists is to tell the CRTC what they want so the CRTC knows what to give them. CAB wants a captioning “standard” so ass-backwards, vague, and slipshod that it is guaranteed to save broadcasters money on an activity they never once, for a minute, wanted to carry out in the first place – providing captioned programming.

This public process is about pushing through a captioning “standard,” and that standard is all about legalizing across-the-board use of el-cheapo scrollup captioning. That is the only goal of the broadcasting side of this process. CRTC mandarins know that, as do their friends at the CAB and their former and future employers in the broadcast sector.

Unfortunately for these groups, I have all the facts.

The CRTC, as an arm of the government, is a public entity. The current process is a public one. The CAB, broadcasters, and others are engaged in a process to affect public policy, the most important detail of which would be the imposition, on all broadcasters for the rest of our natural lives, of a captioning “standard” that permits half-assed captioning at cut-rate prices.

As such, all participants in this process have to be real about something: You’re affecting a public process and your statements and actions will be debated and critiqued publicly.

In Web accessibility, this proceeding has been one of the ignorant leading the stupid.

The CRTC has just enough knowledge of Web accessibility to be dangerous. Unfortunately, those dangers involve indefinitely altering the legal landscape of broadcasting and the Web, so this has serious implications.

The CRTC could not even figure out that the World Wide Web Consortium publishes many “guidelines.” The only guidelines that matter are the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG, which has a pronunciation: wikkag). There are two versions, WCAG 1.0 (released 1999) and WCAG 2.0 (released December 2008). WCAG 1 is still in effect and can still be used by Web sites, ideally in conjunction with the independently developed WCAG Samurai Errata. WCAG 1 and 2 both have three compliance levels. It’s impossible in practice to comply with WCAG 1 Priority 3; WCAG 1 Priority 1 is good enough for many sites.

Hence, every time the CRTC brought up the whole issue of “the W3C guidelines,” the phrase was itself so vague and overlarge it could mean anything. Broadcasters and telcos jumped on this chance to respond, in effect, that if the CRTC is asking the world (compliance with “W3C guidelines”) then of course that would cost the world and is probably impossible in the first place. While these are lies, they are lies the CRTC induced.

The CRTC could have avoided the whole problem had it had enough knowledge and acumen to carefully specify what it was talking about. Compliance with WCAG 1 Priority 1? WCAG 2, any level? The whole discussion was poisoned by the CRTC’s own incompetence and inability to focus the discussion.

Note that all Web-accessibility guidelines, regardless of source or level, require captioning and audio description of video. To comply with WCAG, for example, you must caption and describe your video. (While some versions of WCAG permit transcripts, transcripts do not provide accessibility and cannot be included in any CRTC regulation.) Neither the CRTC nor broadcasters understands what they’re getting into.

WCAG has existed for ten years, and Web accessibility as a field has been well understood since at least 2002. I wrote one of the books on the topic, Building Accessible Websites. There’s a vast repertoire of online articles, guides, standards, and podcasts on Web accessibility and a longstanding lecture and conference circuit across many countries. Web accessibility is a subset of the Web-standards movement, which espouses the creation of Web sites in strict or compliance with published standards.

Yet the CRTC and broadcasters are, as ever, last to know. It is not the fault of people with disabilities that CRTC commissioners and mandarins, and their former and future employers in the broadcasting sector, did not notice the obvious. Nor is it disabled people’s fault that broadcasters spent a decade making exactly the wrong market choice over and over again, hiring incompetent developers who do not know the first thing about Web standards and Web accessibility.

Broadcasters chose – repeatedly, over a decade – to hire developers who thought “the Internet” was a blue e on their Windows desktop; who build sites with tables for layout “font tags,” and Flash; who froze themselves, like bugs in amber, in a bygone era. Broadcasters hired developers whose skills formed over a few months in 1997 and never budged an inch. Broadcasters’ on-staff Web developers would have a hard time producing a Web page with the code quality of this document. Broadcasters made their beds and now they have to lie in them.

A decade’s incompetent and substandard Web development eventually costs. Since it is well known that accessible sites are more usable to all people and represent colossal return on investment, broadcasters are in no position to whine about how much it will cost to fix their broken sites. They chose to publish broken sites in the first place, and chose to heap stupidity atop ineptitude by refusing to publish accessible sites. Those are exactly the kinds of sites that pay for themselves, but the option to implement accessibility up front has long since passed. Broadcasters must now join the 21st century and build sites the way grownups do.

A set of experienced developers and authors from outside Canada has already submitted to this proceeding a statement that broadcasters and telcos should already have known how to code to standards all along.

Or, more precisely, regulate the Web. The CRTC failed to be upfront about what it proposes to do – regulate the Internet. While that prospect may be at odds with the oft-quoted 1999 decision to forego regulating the Internet, we don’t live in the ’90s anymore. The legal rights of people with disabilities, as expressed in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Human Rights Act, trump a decade-old policy document, not to mention the broadcasting oligopoly, net activists, libertarians, Objectivists, and other cultists who cling to the delusion that their own opinions about how the Internet should evolve trump what must legally occur to secure the rights of disabled people.

These themes were fully explored in my article for A List Apart, “This Is How the Web Gets Regulated.”

In any event, the proposed regulation will not take the form that activists warn against – Chinese-style government censorship of personal expression. We are talking about a filthy-rich oligopoly of multi-million-dollar (and, in some cases, multi-billion-dollar) corporations publishing on the Web. All they’d be required to do is make such publication accessible to people with disabilities. There would be no new restraints on content, and individual Canadian citizens’ expression rights would not be affected.

The regulation in question would require text, graphics, and interactivity to be accessible and would require captioning and description of video. The former requirements concentrate on markup and scripting, the latter on post-facto additions to existing files. No aspect of such regulation infringes on or limits broadcasting conglomerates’ freedom of expression, or anybody else’s. In short, in a regulated broadcasting environment and under the Charter and the Human Rights Act, no, there is no such thing as a broadcaster’s legal right to publish inaccessible content.

When we talk about “regulating the Internet,” the context here is Web sites and online video. The latter may be served through “sites” like iTunes that are not Web sites in the first place. The Canadian broadcasting oligopoly cannot be permitted to offload inaccessibility onto third-party providers like Apple. Content of all kinds, including video, must be made accessible wherever and however it might be made available to Canadians, whether on broadcasters’ own Web sites, on iTunes, on Hulu-like video players, on net-connected TiVos and digital video recorders, and everywhere else.

Broadcasters will say anything, without limitation, to evade their legal responsibilities to people with disabilities, and in fact the 30-year history of captioning in Canada has been a litany of lies, half-truths, and disingenuousness. CRTC commissioners and mandarins, perhaps understandably worried they’ll have nowhere to go once they leave the CRTC, believe every lie that broadcasters whisper in their ears.

The latest such lie? Online captioning is impossible or just too difficult, and – wait for it! – captions are too small. These claims are, of course, bullshit.

All player formats – QuickTime, Real, Windows Media, and Flash – support closed captioning, often in numerous ways. All player formats without exception support open captioning. Hence, no, online captioning is not “impossible.”

It is “difficult” to caption online video compared to captioning a DigiBeta tape for broadcast, but it is not “too difficult.” I have firsthand knowledge, since I set up a system to publish open-captioned CBC News segments online in 2002 for a total hardware cost of $600 U.S. (We simply decoded Line 21 closed captions – often a reasonable approach.) Television closed captioning can, with difficulty, be translated to online formats. Hulu and iTunes manage it. Would online captioning be so difficult it would constitute undue hardship? No – it’s already being done in the commercial sector and had already been done in public broadcasting.

Next, typography. Television captioning decoded and burned into the picture results in captions the same relative size on the online screen as they are on TV. Closed captioning can use different fonts and can, in fact, be proportionately larger than TV captioning. Online devices are closer to the eyes than far-off TV screens and occupy more of the visual field, resulting in shorter saccades.

Much of this has been well discussed online, as at a Web site neither the CRTC nor broadcasters has bothered to look up, Screenfont.CA. Broadcasters would prefer to lie through their teeth than do actual research, the latter being almost as unpalatable as actually living up to their legal responsibilities to disabled people.

Scrollup captioning is just fine on all programming and cigarettes don’t cause cancer.

Offline captioning is carried out by small-time operators and, increasingly, by taperooms and postproduction houses. Most captioners are females in their 20s with liberal-arts degrees they can’t sell in the job market. That means captioners are a monoculture: They lack life experience, they aren’t going to stick with the job, and they make the same kinds of mistakes. (The latter means they also see right through those same mistakes on the rare occasion they proof the work of another, functionally interchangeable, captioner.)

There is a widespread delusion that a degree in English literature has relevance to captioning. It doesn’t. It equips you to write turgid papers on themes and structure, but does not equip you to transcribe and caption Just for Laughs: Gags, Keys to the VIP, or Trailer Park Boys (who, it should be pointed out, seem to do their own captioning). Real captioners are professional writers or copy-editors or proofreaders, or can pass real-world tests.

There are no standards, but every company acts like it knows what it’s doing and fiercely defends its own allegedly distinct – and obviously superior – method of captioning.

Captioners earn next to nothing. Real-time captioners are especially hard hit; while their unique skills take a huge toll on their arms and hands, filthy-rich broadcasters have spent decades tightening the screws on real-time captioners, continually lowballing prices. As such, the cheapest operators (like BCCS, but we’ll get to them later) eat up market share.

Captioners toil in obscurity. But they also know that nothing whatsoever will happen to them if they do a lousy job, so they forge right ahead and do that.

A few broadcasters have in-house captioning departments, though CanWest is firing nearly all of its own such department. Most of these are departments labour under two burdens – ideology and a rampant insistence on quickest turnover at lowest cost. It was in-house caption departments, as at Corus and Alliance, that gave us all-scrollup captioning on every possible program. It was also these in-house operations that decided to rewrite the rules of the English language to suit themselves – resulting in everything from use of British spellings to bizarre rendering of numbers to an atheist insistence that God, Lord, and Jesus Christ must never be capitalized.

Incidentally, in the world of Canadian captioning, the Caps Lock key is always depressed.

French-language broadcasters and captioners cling to the myth of French supremacy. Their language is so very much more complex than the debased, patois-like gobbledygook que les anglophones parlent. That makes French shows impossible to caption, or, if not impossible, so difficult that we can only manage a couple of captioned shows here and there. These superior beings’ language skills are so advanced compared to ours that French-speaking captioners are always qualified to caption English shows, but the converse is never true.

Absolutely any signals whatsoever inserted into Line 21 qualify as “captioning.” Anything goes.

That’s what’s really happening.

CAB published a captioning “standard,” the product of a secret backroom deal, in 2004. It wasn’t a standard at all but a collection of half-assed practices preferred by incumbent Canadian captioners. It was a complete failure in the marketplace. Most third-party captioners (including the largest, Mijo/Comprehensive) ignored it outright. Practically nobody claimed to be compliant with the standard, which in any event was so loose and vague that completely different captions could be deemed to comply. An all-scrollup operation could comply as easily as a real operation that captioned fictional narrative programming in pop-on; all-upper-case captioning complied as handily as mixed-case. A standard that comprises both matter and antimatter isn’t a standard at all.

Since captioning is all about doing what we already know doesn’t work over and over again, the CRTC “invited” the CAB to form another panel drawn from the same anti–talent pool of people who had been screwing up captioning all along. Their task? Write another captioning “standard.” They would work in secret and present their so-called standard as a fait accompli. CAB would have the last word on any public comments.

I thought 2008 was the year that industry self-regulation was finally proven not to work. The broadcasters that gave us no captioning, not enough captioning, or lousy captioning are exactly the worst people to write a so-called standard. It’s like asking the tobacco industry to write the standard for cigarette safety.

It gets worse: The so-called standards committees were stacked with industry hacks. They outnumbered representatives of deaf and hard-of-hearing groups and came disproportionately from companies that caption everything or nearly everything in scrollup.

The chair of both committees comes from Parliament. Somehow somebody decided that Parliamentary experience has something to do with captioning. It doesn’t. The chair probably has a conflict of interest: He was probably involved in a decision to pay CRIM or one of its for-profit offshoots to use its speaker-dependent voice-recognition system to caption the French House of Commons feed.

Wendy Fisher of Corus Entertainment runs an all-scrollup shop.

Brian Hallahan runs the second-worst captioner in Canada, Broadcast Captioning & Consulting Services Inc. His company has barely ever met a program it couldn’t caption – badly – in scrollup. This is a company that can’t even transcribe.

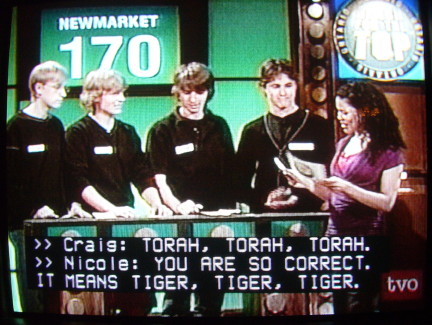

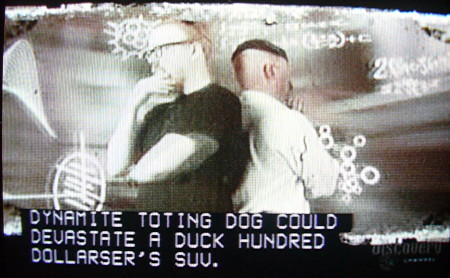

It’s actually Tora! Tora! Tora! (Who knew the Japanese were really Jews?)

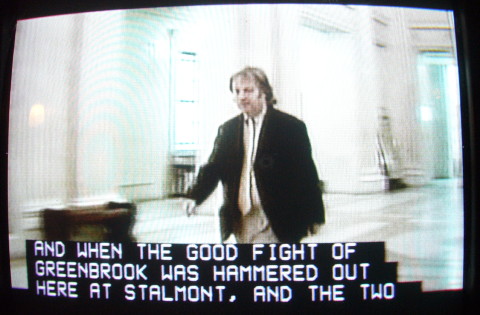

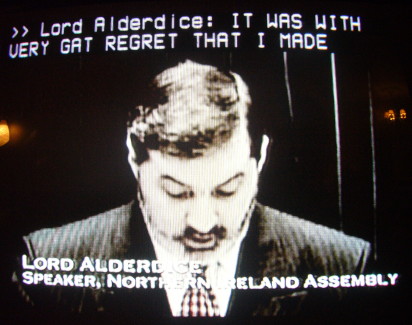

That’s actually the Good Friday Accord.

Putting Hallahan on the committee is like asking Henry Kissinger to investigate 9/11.

And astonishingly, BCCS gets two seats – his “assistant,” Christina Ricci, is also on the committee. BCCS is the sole captioner on the committee and it gets two seats.

BCCS has two main client groups: Broadcasters that loathe captioning (Quebecor, Rogers) and those that cloak their loathing of captioning in claims of poverty (TVO). BCCS is a company held in such low regard that not one but two broadcasters’ executives told me to my face they would never hire BCCS under any conditions.

Deaf groups get two seats. A captioning lobby group gets one more seat. Assuming the chair votes only to break ties, that leaves them outvoted six to two on the English side and six to one on the French side. Industry hacks can do whatever they want and deaf groups and captioning lobbyists can do nothing about it.

The company Voice to Visual Inc. has no profile whatsoever in the captioning business and the presence of its representative, William Jahnke, seems inexplicable, except to paper the house.

Pierre Dumouchel from CRIM has a clear conflict of interest, as his researchers have capitalized on the lie, reiterated by French broadcasters for decades, that live captioning is just too difficult in the language of Molière (also of Allô Police).

Instead of training stenotypists on either of the two French-language systems in existence, French broadcasters lied through their teeth, dithering for decades – a period in which next to no live captioning was provided for French-language viewers – with approval from easily bamboozled (French-speaking) CRTC mandarins.

And here comes Dumouchel riding in on the white horse of “voice recognition,” which is actually speaker-dependent voice recognition. Canadian broadcasters would love nothing more than to fire every captioner in the country (CanWest has almost accomplished that in-house) and replace them with computers. (Set it and forget it!)

Broadcasters react with Pavlovian awe to the phrase “voice recognition,” believing it will solve their problems. They believed it when Beverlyy Ostafichuk Milligan peddled a system optimistically named VoiceWriter that didn’t work, and they believe Dumouchel when he peddles his own system. As a vendor trying to take over the entire sphere of French-language live captioning and as much of the English side as he can manage, Dumouchel has a financial interest that occludes any research interest he may otherwise hold.

Additionally, Quebecor found so little use in the committee that it quit. While Quebecor is notorious for its outright loathing of captioning, this is hardly a vote of confidence for the committee.

The CRTC, the CAB, and broadcasters don’t like TV and do not watch captioning. They also aren’t very literate, and they certainly aren’t deaf. They don’t understand why scrollup doesn’t work.

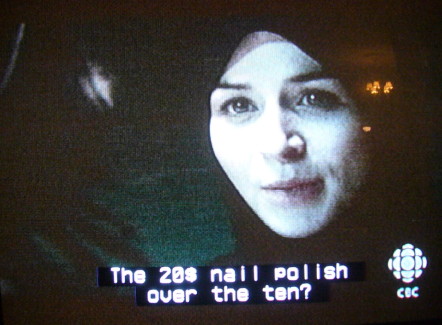

You can’t watch the program. Research by Carl Jensema et al. has shown that, not surprisingly, most of the time captioning viewers are looking at captions. The rest of the time, you’re watching the action via peripheral vision and by occasional fixations outside the caption block. But Jensema assured me “I don’t think I’ve published any eye-movement articles involving scrolling captions.”

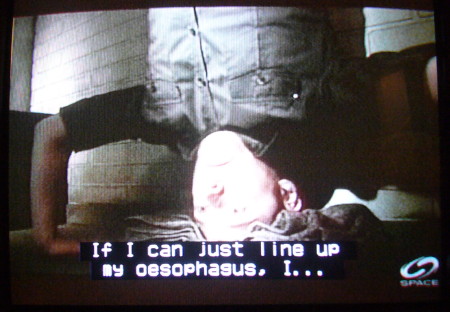

Our ability to look away from captions is predicated on the idea that a caption appears, sits there for a while, and is replaced by another caption or nothing. Scrollup captioning presents continuously extruding text that must be monitored in real time. Pop-on captioning is an image; scrollup captioning is an animation.

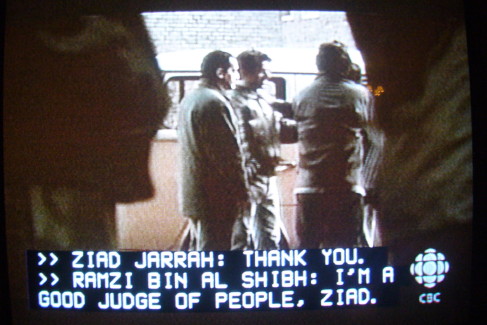

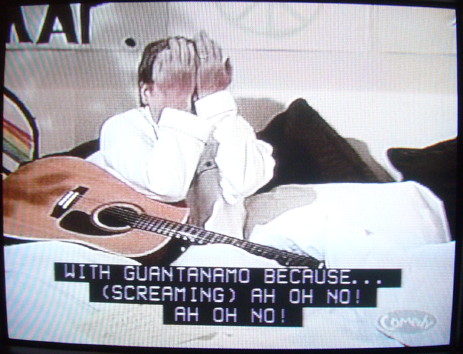

You can’t position captions. It’s technically possible, but it isn’t done. The result is you cannot show who’s speaking by position alone. The brute-force “remedy” for this problem is to ID every speaker, leading to redundancy atop illegibility:

You can’t time captions. Captions must scroll up, begin to be rendered, occupy one or more lines, then repeat the process endlessly. You can’t time this continuous extrusion to conform to the beginning and ending of an event, at least not in practice.

Scrollup clobbers titles. Chyrons, keys, and subtitles are simply destroyed or covered up by scrollup captioning despite the fact that such captions can be placed anywhere onscreen.

No style manual authorizes the use of scrollup captions for fictional narrative programming.

The original CAB “standard” comes as close as it ever does to banning the practice:

Off-line pop-on captions... are the only type of captions well suited to dramas, sitcoms, movies, and music videos, and they are therefore recommended for these types of programming.... Off-line roll-up captions are not well suited to dramas, sitcoms, movies, children’s programs, or music videos, and their use for these types of programming is discouraged.

The Caption Center Manual of Style limits use of scrollup captions to “programs produced very close to airtime or produced live.” (A later clarification states “The rules we have are unwritten and usually involve a discussion between marketing and the client. We have tried to hold a line that says comedies and dramas should be pop-on; news material, documentaries, talk shows, etc. can be roll-up. The grey area in-between frequently comes down to turnaround time and cost.”)

Even the outdated and misguided CCDA style guide (submitted in a letter of 1995.01.04 from Beverlyy Ostafichuk, Canada Caption Inc., under Public Notice CRTC 1994-18) declares: “Traditionally, roll-up captions are used only for live captioning, and offline work is done with pop-on captions.”

Captioning Key: Preferred Styles and Standards (Captioned Films/Videos Program, National Association of the Deaf, 1995) flatly states: “The CFV program requires pop-on captions.”

The ITC Guidance on Standards for Subtitling limits scrollup captions to real-time stenography:

The use of scrolling word-by-word captions for live news can present particular difficulties, especially in the area of retention of information. It is not just a problem of speed, but that the text placed upon moving lines is working against the readers’ natural reading strategy.... During an unscripted live broadcast... the subtitles must be composed, entered, formatted and transmitted in a single pass through the program.

The Australian Television Broadcasting Services (Digital Conversion) Act 1998 Draft Captioning Standards don’t even mention scrollup captioning, presumably because it is axiomatic that the method would be used purely for live events.

The only book currently in print on subtitling (Ivarsson and Carroll 1998) states that neither scrolling nor crawling

systems can be recommended (except possibly where a live subtitling is being broadcast for the hard-of-hearing). The problem with moving text is that the eye concentrates on the text while waiting for the word or phrase to finish and is thus prevented from seeing what is happening in the picture. This does not matter very much if the picture is only showing the news presenter, but if the images are conveying important information, such fixation on the text is disastrous.

People who are used to this system may say that in time you learn to move the eye upwards, take in the picture for a moment and then look down again to read some more of the text. But in that case, what is the advantage of a scrolled system over the “quieter” traditional system?

CTV (né CHUM) stated categorically (CRTC 2006-380) that “roll-up captioning is not well suited to dramatic and certain other types of programming.”

Based purely on the previous evidence, the use of scrollup captions for fictional narrative programs should be prohibited in all cases save for emergencies. The current evidence, which CAB ginned up to show that scrollup was okey-dokey for everyone, proves just the opposite.

Canadian captioning is a mess.

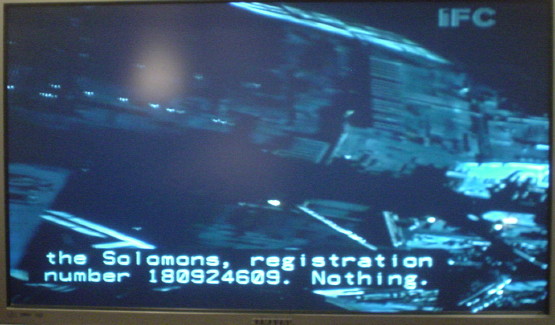

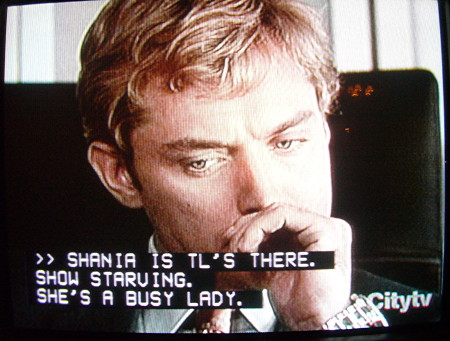

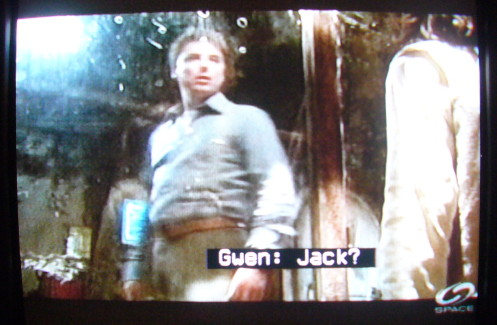

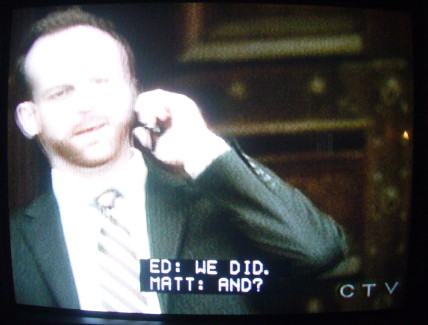

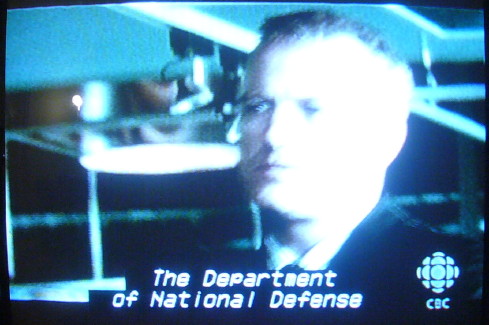

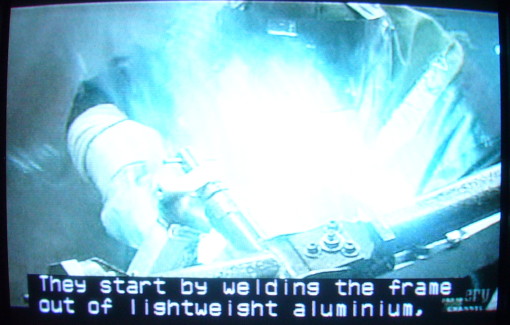

Overuse of scrollup captioning. Broadcasters use scrollup on everything, including fictional narrative programming, music, and subtitled programming. Worst offenders: TVO, Sun TV, all CTV and former Alliance channels. On those last channels, already-captioned programming is recaptioned in scrollup. Even though four pop-on-captioned versions of Alien exist, for example, Alliance recaptioned it in scrollup:

Use of bizarre centred scrollup captioning. Canada’s richest broadcaster, CTV, hired Canada’s worst captioner (Look Smart Captioning, with no Web site or published phone number), which captions nearly every show in centred scrollup.

Misuse of real-time captioning. Real-time captioning is used on shows that provably are not live, including most episodes of prominent Discovery Channel series like Mythbusters and Dirty Jobs.

Live shows retain real-time captions even when repeated (e.g., repeats of those Discovery series even many years later; CBC Sports Saturday repeats airing overnight Monday).

Real-time captioning is used on fictional narrative programming for which pop-on captions already exist, an explicit Rogers policy at CITY-TV.

Real-time stenotypists are essentially never provided with proper names in advance. Just try understanding the Sri Lanka vs. Pakistan cricket match under those conditions .

All-upper-case captioning. Thirty years on, captions continue to SHOUT; no other extended English copy uses capitals. Some captioners caption English in all caps, French in mixed case (e.g., Mijo/Comprehensive). Captioners are still unclear on how to caption in all upper case and mixed case; speaker identification continues to baffle them.

CBC switched from all caps to mixed case back to all caps within the last year and a half.

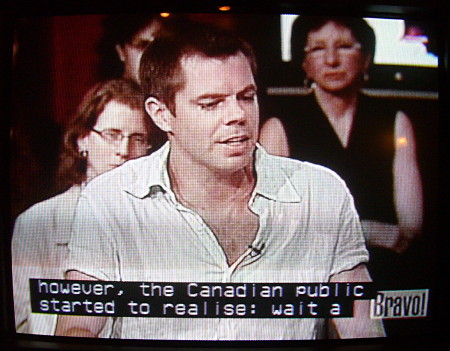

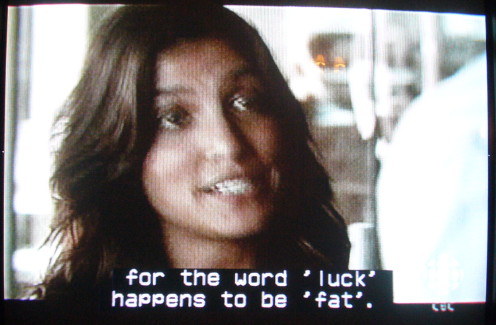

Canadian English is not used. Canadian captioners work under the delusion that Canadian spelling is not unique. They use American spelling (and quotation marks, whose use Canada shares):

Or British –

Or a bastardized version filtered through Francophone ears that cannot even hear English word endings:

Return of teleprompter captioning. CBC uses a banned captioning method – teleprompter or electronic newsroom (ENR) captioning – for weather breaks within freestanding programming.

In attempting to impose a captioning “standard” cooked up in secret by the industry it claims to regulate, the CRTC would, de facto, regulate individual captioning companies, over which it has no legal jurisdiction.

Thirty years later and after a string of billion-dollar buyouts of each other, TV executives wearing diamond cufflinks have the gall to claim that captioning is expensive. As captioning is an accommodation provided under the auspices of the Charter and, more relevantly here, the Canadian Human Rights Act, the only criterion related to cost is that of undue hardship. Undue hardship may occur in marginal cases (e.g., the Knowledge Network), but even then only debatably.

Broadcasters complain about cost and CRTC commissioners coo understandingly in response. What broadcasters are really saying is “We don’t want to spend a plum nickel on this.” What CRTC commissioners are really saying in return is “Well, we agree with you, but we have to keep up appearances.”

The CRTC has already established that “the cost of offering closed captioning is part of the expense of holding a broadcasting licence” (CRTC 2004-10). Broadcasters have repeatedly testified that, through (fraudulent) captioning sponsorships and presumably other methods, captioning turns a profit. (At Global, “actually the profits on closed captioning were about a million on $5 million.” CTV also admitted, although they didn’t give exact numbers, that they make a profit on captioning.)

While there may be rare edge-case exceptions, the entire discussion of cost is a dodge and a distraction. Broadcasters are richer than God, they benefit from a unique ability to slot their own commercials into programming somebody else paid to produce, and they’ve had 30 years to get used to the idea that one day somebody would force them to caption everything. That day has come.

Let’s start with CAB’s letter to the CRTC dated 2008.11.17.

CAB improperly implicated public broadcasters. CAB – the enforcer lobbyists representing private broadcasters – states that its jury-rigged standard “will apply to all private, public, and educational” broadcasters. It couldn’t possibly: CAB does not represent two of those three categories. While it certainly seems as though the CRTC is taking orders directly from CAB and turning them verbatim into public policy, CAB does not set public policy, at least not nominally.

The CAB committee included Heather Boyce from the CBC, whose presence there is offensive on numerous levels. TVO separately stated that it was awaiting the outcome of this so-called standardization process before cleaning up its abominable captioning; TVO contracts with BCCS and, like the CBC, fails to be a private broadcaster, so it has no business hitching a ride on the CAB’s wagon.

CAB thinks it is testing a new feminine-hygiene spray. Initially, the CAB tried to bullshit the CRTC that the approval of three deaf reps and captioning lobbyists on the two committees would be sufficient to prove their “standard” was worth the paper it was written on. Milquetoast CRTC mandarins later called CAB up and querulously asked if maybe CAB could try something “similar to a focus group.” (Note CRTC’s attempt to evade the public interest by avoiding a paper trail. CAB wrote it down anyway.) We aren’t market-testing a new potato chip here; we are attempting to govern an entire medium of communication.

The basic intellectual fraud of this process was laid bare in its name – a “validation exercise,” i.e., a fait accompli to prove a predetermined outcome.

CAB finally realized real standards cost. CAB admitted it could not even come up with the money to run a focus group without asking for a deadline extension. (CAB, as usual getting whatever it wants, received its requested extension.)

On the CAB’s preliminary report of its working group:

This isn’t about all captioning everywhere. In an act of revisionism blatant even for an industry lobby group, CAB attempts to recast the entire process as one of setting standards for all captioning that airs in Canada, even if produced outside the country (“the [‘standard’] cannot apply only to Canadian programming but to all programming”). This is nonsense: The process is about Canadian captioning, that is, captioning produced in Canada that airs on a licensed Canadian broadcaster. Yet the CAB contradicts itself on this point, stating that broadcasters and captioners (presumably only BCCS) told CAB “they have no control over the format of captioning used in programs Canadian broadcasters acquire from foreign distributors.” Either you control it or you don’t. Since you don’t, we can’t regulate it.

The FCC never ordered “every program” captioned. In another blatant lie masquerading as a minor typing error, CAB claims that U.S. soap operas (or, as CAB calls them, “ ‘soap operas’ ”) are captioned using scrollup “to meet the FCC’s requirement... that every program produced be closed-captioned.” The FCC has an entire flowchart of exemptions to its captioning rules. Not “every” program in the U.S. has to be captioned. Nor do the requirements “only apply to programs produced after January 1, 2006.” (The CAB is advised to review the concept of “pre-rule programming.”)

PAL-format programs arrive with captioning just fine. CAB lies when it states that “foreign programs produced in Europe… must be recaptioned.” No, they don’t – PAL-format teletext captions merely need to be transcoded to NTSC Line 21 captions. CAB member broadcasters air many programs with such captioning. Just watch Little Britain or Life on Mars, among many others.

PAL-format captioning “from such sources France” (sic) could be transcoded.

Note that such transcoding is undesirable due to Europeans’ bizarre and deficient captioning. I defy any Canadian captioning viewer to watch a U.K.-captioned program broadcast here with transcoded captions and claim to have understood and enjoyed it.

Pop-on captioning is not “difficult and costly.” By far the most beloved lie reiterated by the CAB and its members is the mendacious statement that pop-on captioning is “difficult and costly.” They roll this one out whenever they need it – for shows arriving too close to airtime, for European shows, for live shows, and now (or so they hope) for all shows.

Any rationally managed captioning house can turn around a one-hour program (with an approximate 48-minute runtime) in about 18 work hours. This will come as a shock to the CAB, CRTC, and some broadcasters, who still think you need to dick around with videotapes. You don’t. Nonlinear captioning systems – that really means only one system, Swift – became the standard while you weren’t looking. You can start captioning a few seconds after the system begins ingesting the program, and several people can work on different ingested segements of the same show all at once. Nor do you need to encode a tape: Systems can simply play back captions as a program plays back.

If your show arrives later than you’d like, assign more than one captioner to handle it. During the broadcast day, this can’t happen more than once or twice (more like once a week), and surely it would never represent undue hardship, the sole standard by which cost may be evaluated under human-rights law.

We aren’t Americans. CAB devotes pages and pages to a demolition of a request by its supposed partner, the Canadian Association of the Deaf, to adopt standards submitted by TDI to the FCC. The CAB is ostensibly the Canadian Association of Broadcasters, but, perhaps because the entire raison d’être of its membership is to rebroadcast American programming, CAB has somehow overlooked the fact that Canada is a sovereign country and we aren’t bound by FCC rulings. How the FCC responded to TDI’s submission may be of interest, but it says nothing about how we should respond to it.

Digital switchover is not “HD” switchover. CAB seems as confused by the U.S. digital switchover as Americans are. After 2009.02.17, over-the-air broadcasting will be digital, but it won’t be “only in HD,” as CAB falsely claims.

Quality of prerecorded captioning is an issue. CAB claims that “all intervenors” in this proceeding “indicated” that prerecorded captioning has no quality problems. This too is a baldfaced lie, but the untruth is the lack of quality problems, not the attribution of the statement. CAB has brilliantly set up this statement to be so difficult to refute that nobody will bother. But let’s start here:

The use of scrollup captioning on prerecorded programming is a quality issue.

All-caps captioning is a quality issue.

Caption division, timing, placement, and orthography are quality issues. Accuracy of transcription is a quality issue. (Caption-naïve and -hostile people think captioning is about nothing more than accuracy of transcription.) Blinkrate, character encoding, durability of caption encoding, and transcoding to 708 are quality issues.

If caption quality is, as CAB asserts, not an issue, why do we need their standard? Why are we having this proceeding at all if everything’s A-OK?

Either one size fits all or it doesn’t. CAB wants us to believe its so-called standard has to apply to every smidgen of programming aired in Canada, even by broadcasters it doesn’t represent and even if it comes from outside our borders. Yet it wants Showcase and Séries+ grouped into one category of “difficulty, insofar as captioning is concerned” and the Weather Network, TSN, Météomédia, and RDS in another category. You want one standard? Then stick to one standard. You don’t get two standards, or four, or 20.

Self-regulation failed so badly it got us here in the first place. CAB recommends that every broadcaster police itself. Gee, that worked real well in the financial industry. Next the broadcasters are gonna ask for a bailout.

Self-regulation fails when it comes to accessibility for persons with disabilities; if it didn’t fail, we wouldn’t need laws and regulations. Broadcasters have worked diligently for an entire generation to deny disabled viewers their legal and constitutional rights. Self-regulation is half the problem; the CRTC’s failed regulation is the other half. Again: Captioning is all about doing what we already know doesn’t work over and over again, but we aren’t going to let the industry regulate itself.

The fact that the CAD (which really just means Jim Roots) refused to sign on to the CAB’s plan to rubber-stamp across-the-board use of scrollup captioning dooms the entire plan. It is shocking that the Canadian Hard of Hearing Association did not voice similar objections, but that has the salutary effect of telling us we can never trust them again when they talk about captioning.

The entire Francophone bloc of the committee backed pop-on captioning for fictional narrative programming. The only holdouts were the CAB itself; cheapskate anglo broadcasters who loathe captioning in the first place, or who always use scrollup anyway; and the sole captioner on the committee, an almost-all-scrollup shop.

The former CRTC standard for captioning – 90% of the broadcast day – looked good to outsiders, who do not fundamentally believe that deaf people are equal to hearing people. But in practice it meant that broadcasters could take most of the summer off with no captioning and still meet the standard. 36.5 full days could have no captioning at all; as the broadcast day is at most 18 hours long, an additional over 40 days’ worth of uncaptioned airtime is permissible just via the definition of that term. The current “90%” captioning standard actually permits two and a half months per year of zero captioning.

The legal tenability of a level of caption provision below 100% was put to rest forever after the decision in Vlug v. CBC, which required CBC Television and Newsworld to caption every second of their broadcast day save for “glitches.” CBC and others have maintained that outside commercials don’t have to be captioned, but this is a lie. The ruling stated:

Even access to television commercials cannot, in my view, be characterized as trivial: whether we like it or not, advertising has a significant place in the fabric of popular culture.... The CBC’s English-language network and Newsworld shall caption all of their television programming, including television shows, commercials, promos and unscheduled news flashes, from sign on until sign off....

As in any human endeavour, there will inevitably be glitches with respect to the delivery of captioning. As is the case with both audio and visual transmissions, these should be the exceptions. The rule should be full captioning.

And that is the rule. It’s just that everyone but the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal and Henry Vlug are in denial about it.

The CRTC’s subsequent captioning policy required 100% captioning, but only of the broadcast day. In other words, it required 75% captioning, and it exempted commercials. The CRTC knowingly defied the existing jurisprudence on what constitutes adequate accommodation of people with hearing loss. We were supposed to be impressed, but the CRTC’s policy did not and will not result in the same accessibility to television broadcasting for deaf people that hearing people enjoy. As such, the policy is prima facie discriminatory and illegal.

Additionally, CRTC precedent forces it to require that all forms of programming, including commercials, be captioned. CRTC has previously required captioning of preschool programming (CRTC 2004-27) and of VJ throws on MuchMusic. (In the latter case [CRTC 2006-380], CRTC required MuchMusic “to closed-caption 90% of all non-music programming, including presentations by program hosts, aired during the broadcast day in each of the first five years of the licence term. Beginning in the sixth year of its licence, the Commission requires the licensee to close caption 90% of all programming, including music videos.”)

Nonetheless, CBC has put some effort into captioning everything on the two affected networks save for outside commercials. They are wrong to exempt those, but the efforts are paying off: About four years later, it is uncommon to find uncaptioned programming on CBC. I should know; I’m the one who keeps notes. CBC also uses incorrect caption formats (as with teleprompter captioning).

Based on my inspection of the CBC employee database, CBC manages this with four captioners and one caption coordinator.

CBC has proven it is viable to provide near-100% captioning around the clock on more than one channel every day of the year indefinitely. It is a lie to contend that such a captioning level is impossible. It’s already being done. It’s been done for years – while you weren’t noticing, or while you pretended not to notice, or while you claimed it was impossible.

Now: What does “100% captioning” mean? It means 99.999% captioning or five-nines captioning. The FCC engaged in a consultation concerning increased captioning requirements in the U.S. in 2005. In its filing, HBO stated (emphasis added):

HBO’s quality-control program monitors 16 categories of potential technical issues associated with video, audio and closed captioning, the occurrence of any one of which is considered a disruption to the service. HBO’s goal is to have each of the 30 linear programming feeds it originates experience no more than 5.5 minutes of programming disruption per year – a reliability factor of more than 99.999%. Over the past two and a half years, more than 25 of HBO’s programming feeds have met this reliability goal consistently. Those linear feeds that fell short of the goal missed it by an insignificant amount on an annual basis....

HBO has found that closed-captioning errors on its feeds account for less than 10% of all disruption events (i.e., less than 30 seconds per year). In fact, in HBO’s experience, the errors in closed captioning are fewer than the miniscule amount of audio discrepancies. [...]

The actually viable tolerance for 100% captioning is 0.001% error. That means five-nines or 99.999% captioning, an existing standard already in place at HBO. That figure is not a minimum allowance of uncaptioned programming; it is the headroom necessary to account for the fact that computers sometimes crash and staff are sometimes asleep at the switch.

99.999% captioning means 0.001% of programming can air without captions. Out of 8,760 hours in a 365-day year, 0.0876 hours may air without captioning. That’s five minutes. Video and audio don’t crash for more than five minutes a year; why should captioning? Welcome to the world of equality.

The CRTC must ban the use of scrollup captioning on fictional narrative programming, music, subtitled programming, and other genres to which it is antithetical. The use of real-time captioning must be banned on programs that provably are not live, and on all reruns.

There is ample precedent for such a measure. After a decade and a half of not even noticing what was going on right under their noses, CRTC mandarins finally figured out that the only way to caption genuinely live shows is to use real-time captioning. The technology that broadcasters were using to dodge real-time captioning – namely teleprompter or ENR captioning – was a nice cheap system. To the uninitiated, to barely-literate broadcasting executives, and to others who just wanted the whole thing handled and done with, ENR appeared to caption a program.

It did not. ENR captioning was not and cannot constitute transcription of the spoken word. The CRTC came to its senses and banned the use of ENR captioning for live programs in in Public Notice CRTC 1995-48. That ruling stated broadcasters must use “either real-time captioning or another technology capable of producing high-quality captioning for live programming.” Why? “[R]eal-time captioning of live programming… is considered by deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers to be far preferable to live-display captioning, is no longer cost-prohibitive and will continue to decrease in cost over the next few years.”

In the current proceeding, exactly the same conditions apply: Captioning viewers demonstrably loathe scrollup captioning on fictional narrative programming and other genres, and pop-on captioning isn’t expensive. (Remember, “expensive” means “incurs undue hardship.” The CRTC has already ruled that captioning is part of the cost of doing business.)

It should be noted that even the broadcasters who are now lobbying to use an unsuitable captioning style have had to backtrack on the use of other such styles in the past. CTV Newsnet Licence Renewal Supplementary Brief (2002): “Our original business plan assumed that our newsroom computer system would create captions from scripts at no additional cost, and that voice-recognition captioning” – that means Ostafichuk’s failed VoiceWriter system – “would be available for live coverage. Both of these systems have been inadequate and we have needed full-time transcribers.”

The Commission and broadcasters already have precedent available to them concerning the banning or elimination of unsuitable captioning methods. Hence the CRTC has an affirmative obligation to reapply the same principles and ban the use of scrollup captioning for fictional narrative programming.

Audio description is really an afterthought in this proceeding, the broadcast side of which is all about ramming through a fake standard.

The claimed research report on audio description completed by Connectus did not consult the largest provider of audio description in Canada, Galaviz & Hauber Productions. It claimed that some things are impossible that Galaviz & Hauber Productions can do and has done – e.g., overnight or same-day turnaround of described programming.

CanWest claims that turnaround time must be taken into account when considering audio description. CanWest is one of the clients that uses Galaviz & Hauber Productions for quick-turnaround jobs.

Another option is to emulate the FCC – usually an option favoured by the CAB – and allow broadcasters to use certain captioning forms but not count them. In an Order on Reconsideration of MM Docket No. 95-176, dated 1998.09.17, the Federal Communications Commission agreed with intervenors that ENR captioning is inferior to real-time captioning for live news. It also agreed that ENR captioning is better than nothing some of the time. To strike a balance, the FCC ruled that larger broadcasters could use ENR but couldn’t count it toward their required captioning hours. The Order, at ¶39, states that:

the four major national broadcast networks (i.e., ABC, CBS, Fox and NBC), broadcast stations affiliated with these networks in the top 25 television markets..., and nonbroadcast networks serving 50% or more of the total number of multichannel video programming distributor... households... will not be allowed to count ENR[-]captioned programming toward compliance with captioning requirements.

Here, broadcasters could use any of the prohibited forms mentioned above, but could not count them in their captioning totals. This plan accommodates genuine emergencies.

Well, here’s an alternative: Require scrollup captioning everywhere and ban pop-on captioning everywhere. If, as CAB insists, scrollup is just as good as pop-on and ever so much cheaper, be honest with yourselves and go all the way. If it’s really that good, kill off the rival.